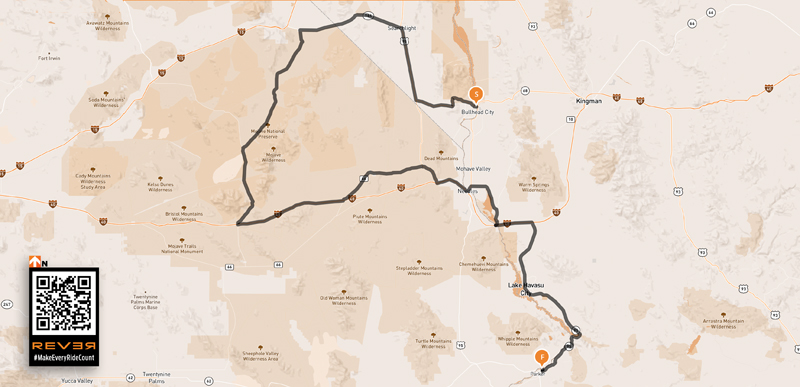

Covering three states and several desert ecosystems, this ride was a survey of contrasts, from arid sand dunes to thriving wetlands, whimsical Joshua trees to towering palms, bustling humanity to sublime solitude. An exploration of the Mojave National Preserve and lower Colorado River was just what the doctor ordered for the off-season riding blues. My timing, at the tail end of fall, was perfect as the region’s summer inferno had cooled into near-perfect riding weather.

Walking, fully geared up and helmet in hand, through the Laughlin, Nevada, casino, it struck me how many people were tugging on slot machine arms at 7 a.m. The only handles I would be pulling were the ones bolted to the triple clamp on my BMW GS. While satisfied with the casino buffet and grudgingly entertained by the Queen tribute band the night before, Laughlin was simply my staging point for a ride through some of the most subtly beautiful scenery in the Southwest.

My westward ascent out of the neon-lit gambling community on the banks of the Colorado was immediate and welcome. Riding on Veterans Memorial Highway (U.S. Route 95), I passed through the tiny town of Cal-Nev-Ari, named after three states in close proximity and, fittingly, the same three I would navigate on this trip.

Once out of the Colorado River Valley, I rode through the beautiful desert “forest” on Joshua Tree Highway (Nevada Route 164). As if conjured from the mind of Dr. Seuss, the Joshua trees seemed to have a sense of humor, each with its own stylized take on what it means to be a tree. The highway crossed into California near Nipton, a historic railroad town dating to 1905. If the Joshua trees had a sense of humor, then Nipton was in on the joke. Interspersed among the town’s small general store, restaurant, hotel and cluster of “eco cabins” are metal art sculptures and classic cars wearing bright, wild paint jobs.

A few miles west of Nipton, I turned south into the Mojave National Preserve. After riding through low shrub and sandy desert terrain, I rolled into another beautiful Joshua tree forest. Traffic was nonexistent, and I made several jaunts on sandy side roads to delve even further into the desert solitude. Deep sand sections challenged my street-biased dual-sport tires, but the preserve is a good playground for an adventure bike in any configuration. It’s important to stick to established and open roads in the preserve, so I kept an eagle eye out for wilderness boundaries.

After stopping to explore a rustic, timber-fenced cattle corral, the first evidence of human habitation was the ghost town of Cima. A former water stop for trains laboring up the long Kelso Valley incline, it’s now home to a sometimes-open store and a few crumbling historic buildings. Continuing south into the heart of the preserve, the Joshua trees soon faded away and the forever views of the open desert emerged. Much of the preserve’s 1.6 million acres was visible in panorama on this stretch. It was the kind of riding that allowed for an open throttle and a free mind. Other than dodging a few sand drifts and tumble weeds, I welcomed the time to think and just ride. On the horizon, golden sand dunes shimmered in the morning sunlight and invited me onward.

After paralleling a train track, I pulled into a cluster of languishing historic buildings with a beautiful red tile-roofed centerpiece. The Kelso Depot opened its doors in 1924 and was a transportation hotspot until the early 1960s, and the surrounding community had 2,000 residents during the railroad’s boom years. Following its heyday, the depot sat empty for years. After nearly being razed in the early 1990s, it is now a beautifully restored visitor center for the Mojave National Preserve. I walked the park-like grounds, discussed the area’s history with a park ranger in the depot’s lobby and took in Kelso’s oasis-like ambiance.

Leaving the depot, I rode past the Kelso Dunes that I had been eyeing for miles. This impressive pile of sand rises 650 feet above the desert floor and covers 45 square miles. It’s also a prime habitat for the desert tortoise, and signage warns to keep an eye out for the big slow-movers on the roadway.

Beyond the dunes the road got more winding and outcroppings of stone dominated the terrain. After a short stint on Interstate 40, I caught old Route 66 through Goffs on my way back to the Colorado River. The river defines the state line, and crossing it took me into Arizona, where my route followed the southern flow of the river. Route 95 brought a scenic mix of desert straights and rocky mountain passes.

Sitting on the bank of its namesake reservoir, Lake Havasu City is fed by the cold waters of the Colorado. Spanning a short portion of the lake is the city’s most notable and incongruous feature. In the heart of the city, I found myself riding in the shadows of several waving Union Jacks. Had the British conquered Arizona? No, but I did ride my GS over a massive stone bridge that once arched over the River Thames. London Bridge was built in 1830, and in a strange and fascinating move, it was dismantled in 1967 and relocated to Arizona. A heavy undertaking by any measure, it was rebuilt stone-by-stone over a period of three years and now connects the city to an island in the lake.

Continuing south on the 95, the winding and diverse river valley made for a fantastic near-winter ride. The Colorado River cuts a stark and beautiful visual contrast between the high-volume blue of the water and the muted browns of the desert. As my route made a turn from southeast to southwest, it made an environmental turn as well. In the heart of the desert is another contrast — a wetlands area teeming with life. The Bill Williams River National Wildlife Refuge is a shag carpet of living, vibrant greens at the tip of the big toe of the Havasu reservoir.

Next came a short spur to see the structure that makes Havasu a lake. Built in the 1930s, Parker Dam is a concrete arch-gravity dam across a narrow section of the Colorado. Like an iceberg with only its concrete lip exposed, the true extent of its impressive engineering is underwater. Parker is the deepest dam in the world, and legend has it that enormous catfish feed in the watery depths on both sides of the massive structure.

Beyond the dam is the Parker Strip, one of the most visually striking portions of the ride. The winding road clings to the red-hued rocks that line this stretch of the Colorado River Valley. As I motored on, the river flowed blue and deep on one side while statuesque stone walls rose up to the clean Arizona sky on the other. Watercraft created V-shaped wakes in the Colorado’s flow as aquatic birds flew in the same formation above. It was intriguing to contemplate that the water I was riding beside had already made the bulk of its 1,450-mile trek from the Rocky Mountains of central Colorado, through several states and the Grand Canyon, and ultimately toward Mexico and the Pacific Ocean.

My ride ended at the BlueWater Resort and Casino in Parker, which has a marina, an indoor water park, several restaurants and balcony rooms with great views of the river. Lady Luck had been my passenger on this ride, so I did not test her generosity on the casino floor. I simply watched the changing hues of the sunset over the Colorado and reflected on a truly memorable ride.

Mojave National Preserve: From Neon to Nirvana Photo Gallery: